"The Dirty Pulse": Part 9

So, at this point in the chronology, Lyndell and I had bought and moved into a home in rural Eastern Ontario in July of 2004, in the wee hamlet named Dalkeith. It was our dream home and we both fell in love with it immediately. On nearly an acre of property, it had beautiful garden plots and a greenhouse, a barn/garage, and was a two-story century home with a brand new electrical panel. It just needed some renovations and TLC and we set to work on it immediately.

We did renovations in between tours that were still quite plentiful, but by this point they had shifted focus away from Canada as a whole. We were playing more than 60% of our shows in the US, about 10% in Australia or New Caledonia (an island near Fiji where we toured twice in tropical paradise—rough life!) and the rest in Canada, but mostly in Ontario and Quebec with occasional trips out East or flights to Vancouver. This decision was mostly a result of working with our agency that was US-based and thus well connected south of the border, and was also influenced by Ram Management who wisely advised both shorter distance and shorter duration travel to keep expenditures down.

As I’ve been making references to our touring vans, I should also add that we were now in possession of the most fancy touring van in our long line of touring vans: the Fifth and Final named “Molar.” “Leopold” had had to be retired to the junk yard after replacing its entire transmission in one season only to have something else major happen to it in the next (I can’t remember what!) that was going to cost us another $2000. We decided it was time to put her out to pasture. We bought this white Ford diesel van from a rental company in Montreal that was refreshing its fleet after a year of use. While it was our most expensive vehicle to date, we needed something more reliable. This was also a vehicle that could run on biodiesel. To us, travelling more eco-consciously was more important than the stress of having to pay monthly van payments.

Since moving house, however, rehearsals were a pain. Picking up the drummers in Toronto (Cheryl) or Guelph (Adam) was increasingly frustrating, especially if we were just heading to the New England area. Since we were living in Eastern Ontario, it made no sense to drive 5 hours back West to the Toronto area before heading south into the US. Also, every time we had to work on new songs, we had to schedule extra days in Toronto and overnight visits. We were lucky to have some good friends who didn’t mind the house guests!

Since moving house, however, rehearsals were a pain. Picking up the drummers in Toronto (Cheryl) or Guelph (Adam) was increasingly frustrating, especially if we were just heading to the New England area. Since we were living in Eastern Ontario, it made no sense to drive 5 hours back West to the Toronto area before heading south into the US. Also, every time we had to work on new songs, we had to schedule extra days in Toronto and overnight visits. We were lucky to have some good friends who didn’t mind the house guests!

Still, as an extra option, we started working with another drummer in the area where we lived (another Adam, but this time Adam Lalonde) who filled in on a few gigs for us. Adam was only in his early twenties, but his playing and personality were mature beyond his years. He’s an extremely skilled player and a refreshingly laid-back guy. (He also looked so much like one of my ex-girlfriends that I immediately felt comfortable with him!) We all got along famously from the beginning and I really enjoyed working with Adam. Unfortunately, he didn’t do any recording with us, however.

By this time, we were almost wholly identified as a duo rather than a trio. As a result, it didn’t really matter who played the kit with us. This is partially because of our constant rotation of drummers over the years and partially because we had started to do more duo work after starting to work with the agency. Record sales were dropping off due to having fully entered the digital download era. We simply weren’t grossing enough to afford a drummer all the time. (Commissions to agencies and management combined cut into our income by as much as 40%, as well, so it was a slim period!) What’s more, some of the folk rooms where we were being programmed in were really not interested in having a drum kit rattle their silverware.

So, all of these changes—geography, homesteading, community, service providers, band members—all affected my songwriting and my goals for recording.

The first thing that changed for me was a clear desire to make a record that radio stations would want to play and that would stick in people’s minds. I wanted an accessible, melodically memorable (and dare I say “pop”?) record.

Richard Dermer of Ram Management suggested we work with his colleague and friend Graham Stairs in Toronto who was a producer and manager and an overall veteran of the industry. As an artist who had always done the production on her records herself, I made a very clear choice to work with someone else this time, mainly because I felt that after eight different recording projects (six, if you don’t count the live albums), I felt I had pretty much tapped all of my own studio expertise. It was time to work with someone who knew more than I did about making the best record possible.

When I asked Graham what his first impression was of me and the music, he wrote this:

“I guess my biggest impression of you was that the fact you were so willing to embrace change. In our conversations, my perspective to you was that there was no point in hiring me as a producer unless I could actually produce the songs. At that point you had recorded a number of albums that were, in essence, souvenirs of your live show as opposed to actual “albums”. So, my goal for the album, and you agreed, was to give your audience an album that they could sit down and listen to all the way through, and that it would be a journey. I felt that you had a strong set of eclectic songs and that they each deserved their own unique treatment. My first impression of your rhythm section was that, although they were both good musicians, they were used to playing way too much!”

I didn’t agree with everything that Graham felt about my previous releases. For instance, I didn’t agree (and still don’t) that previous records weren’t “albums” or weren’t thought out thematically as journeys, for instance. That being said, however, I was getting used to not agreeing with my advisors while still analyzing their criticisms or opinions for the possible truths hidden within. For instance, Richard Dermer (Grapham’s friend) and I were rarely on the same page politically and often disagreed on a business level, but I was in a stage in my career where I welcomed this kind of challenge. So, when Graham came in with a strong set of opinions, I respected them even if I didn’t always agree.

As I look back, following advice that didn’t always feel perfectly in-line with my own opinions was the next phase in my career. After all, I felt I had done as much and gone as far as I could go with my own beliefs, so perhaps another’s influence (or a few others’!) could push my career up a notch? It was worth the risk. I have a lot of respect for what both Richard and Graham and even Fleming Artists (my US agency) brought to my career in the way of opportunities, perspective, and challenge. I learned a lot from them all.

I particularly remember the pre-production rehearsals with Graham when we played the songs and he picked them apart, simplifying the many parts that I had a tendency to chuck into a song even though those parts never occurred a second time, for instance! He also pushed Adam and Lyndell to play less, something both of them were not naturally inclined to do! Having been only a trio for so long, often space got misinterpreted as “needing to be filled” when, in reality, a lot of our music really could have used more musical pauses and gaps, less intricacy, more breathing room. Now that I’ve gone through the learning process that “The Dirty Pulse” provided, the space in the music I write now sounds just as musical to my ears as the sound-filled sections.

We recorded at a studio called Monumental Sound, which was owned by Joe Dumphy, who also was our engineer in the sessions. (Joe now owns Revolution Recording in Toronto.) As I was paying both Graham and Joe for the studio time, it was officially the most expensive album project in the whole collection, which was exhausting, mentally, as I watched our line of credit explode at the seams with the costs of the project. I knew it was money well invested, however, but it didn’t make it easier on the artist who was also the business owner!

When I asked Graham about the recording process and any challenges we may have had in his memory, he wrote this:

“The recording of The Dirty Pulse was both a pleasure and a challenge. Monumental Sound was a big, funky studio with a lot of cool vintage gear at our disposal. The engineer/owner, Joe Dunphy, had and has great ears and I have worked with him often since then, being my engineer of choice for certain kinds of projects. As I said, you were willing to explore different arrangements for your songs and, as a result, I was able to bring in outside musicians to flavour the various tracks; the horns, the keyboard player and the background vocalists all adding creative touches to your songs. I felt that we got on a creative roll that sustained itself throughout the recording process and that we ended up with a great album. Of course, it helped that we had, what I felt, was your strongest set of songs to date.”

And, speaking of some of the musical friction that occurred after his pre-production sweep of the songs:

“There was somewhat of a learning curve for the rhythm section as they learned that simpler was sometimes better for the songs. My philosophy is that the playing and the arrangements have to serve the song and that everyone has to check their egos at the door in order to accomplish that. There were some challenges, mostly as a result of the long hours and the bunker mentality of being in close proximity with each other for long periods of time. I recall that the bass player had a difficult time with the reggae feel of one of the songs and, because you were in a relationship with her, it caused some tension at the time. Having said that, overall, I recall everyone rising to the occasion and the end result, I felt, was a career album for you.”

I remember feeling so grateful to Graham for taking the reigns in this regard. After working with people for so long, even as the songwriter and the voice of the project, because their opinions and artistry had always been honoured and showcased, if I pushed for something different or less natural from them, I had already found that I was often met with resistance, as though I was being critical. Of course, that resistance is magnified when you’re also life partners with someone! A lot of Graham’s suggestions for the rhythm section were things that I had wanted as well, and sometimes had directly asked for but had not been granted! Graham’s role as album producer and his outside position as an “expert” and non-member of the band, not to mention his age and experience, all generated a level of respect from Adam and Lyndell that I couldn’t have procured myself.

Don’t get me wrong, though, because I was not exempt from those revisions! My parts, too, needed a lot of clean up, as a guitar player especially. It took a lot of humility but I’m proud of what I learned in that studio experience and I have no regrets whatsoever.

Speaking of “No Regrets” (!), the first track on the record was a co-write with Lyndell, Brenley MacEachern and Lisa MacIsaac (of Madison Violet) and myself. We had a good time jamming regularly with those girls and somehow this song came together. We further developed it into a reggae song, however, and they further developed it into a country song. I love that! I don’t even think we settled on the same name for it!

After co-writing with Lyndell in the very beginning of our musical connection, there was a long gap of several records where we barely did any co-writing at all. This album, however, includes several songs that we wrote together: “Some Fine Day,” “Bliss,” “Witness” and that final remake of our old song “Mental Breakdown” that originally appeared on the album “Can’t Corner Me.”

Each new one was co-written differently, too. Lyndell had written the chorus to “Some Fine Day” and I filled in the verses and arrangement. She had written some beautiful poetry that inspired “Bliss” and I re-worked the words, added some of my own, and wrote the music and arrangements. For “Witness,” she had this amazing bass line that I decided to try to play around and echo/compliment and then the song evolved from there. I wrote the lyrics but she was actively involved in the arrangement.

As a band, we worked on recording and mixing the record for a full three weeks, reserving the final week for the mixing. As he mentioned above, because Graham had his own contacts I was willing to give some players I had never met a chance in the studio. They were the following talents: Sarah McElcheran on trumpet, Colleen Allen on saxophone, Andrew “Shaggy” Ennals on Hammond and Rhodes organ and Mystic & Miranda on backing vocals (a sister team whose voices were like butter). We also invited Cheryl Reid on percussion and drum kit for the song “Thirteen” and “Reinforced Concrete,” and Janine Stoll on backing vocals for “Mental Breakdown” and “Ten Pin.” Graham also played some tambourine for us on “Intervention”! All of them were incredibly talented and added just enough and just the right feel to the songs. It was a winning gamble.

Ember, recording in the isolation "cubby," behind the stacks of beautiful vintage guitars, Monumental Sound

After we were finished the project, I also felt like I had a “career record.” It was the first time that I held one of my completed albums and felt content. So much so, in fact, that I found myself conscious that if it were to be the last record that I’d ever make, I would be happy and satisfied. It was a compelling feeling. After all, 9 albums and 1 DVD was quite possibly enough and I was sure that this record signified a peak, of sorts.

Post-release, the first problem was the fact that we had no more money to sink into promotion. We only had the human power of my label (which, by then, had shrunk in staff members to just me, and an occasional part-timer, April Boultbee, and occasionally Lyndell, although she had mostly stopped working in the office when we moved in 2004) and Ram Management, who were not skilled at promotion and took all their cues and instructions from me. That meant that any intentions for reaching the “right” ears were already compromised.

We did a small national campaign that included servicing digitally to mainstream radio for the first time. We even invested in a radio tracker for that job! Of the 75 mainstream stations across the country who received the music, only 2 expressed interest. One, based in Nova Scotia about two hours south of Halifax, placed us on high rotation and even had us on for an interview when we were out East on tour. The other, near Ottawa, placed us on low rotation and we heard nothing more from them. When I finished that particular angle—encouraged by my management—I was beyond frustrated. I had never had any faith in mainstream radio and here I had wasted several thousand dollars just to find out what I basically already knew: that air time is controlled by the major labels and that I didn’t have enough clout or money to buy any of that airtime out from under them.

By this point, as well, my relationship with my management company was becoming more and more strained due to differences in intended direction and overall politics. By the end of 2006, I negotiated my way out of the 5-year agreement and we went our separate ways. What I’ll always appreciate about Richard Dermer and Ram Management, however, is the encouragement to separate my businesses into a touring company and a record label (incorporating the latter for tax purposes) as well as the insistence on steady project budget balancing, or to hopefully never have to use one project to pay off the next, etc. I’ll surely grant that we both believe in ethical enterprise, but the relationship definitely ended when it should have.

Graham had thoughts on this as well that he shared when I interviewed him about this project. I was surprised to read them, as he was on the outside, but I was also relieved to know that my impressions weren’t isolated:

In retrospect, I’m not sure how you felt about what the album achieved, but I was frustrated that the team around you… didn’t deliver the record. I thought that the album had some commercial potential… My impression was that Richard, although very smart in a lot of areas, was not record label savvy and did not really know how to market and promote a record. So, it was a little frustrating for me to watch from the sidelines and see the album not get the attention I felt it deserved.

I named the album “The Dirty Pulse” because, thanks to living in the countryside and growing our own food, I felt a renewed connection to the earth and nature. We seemed to be tapping into the life source of the land the way a Chinese doctor will listen for one’s life source by placing two fingers on the inside of one’s wrist to seek a person’s various pulse rates.

I named the album “The Dirty Pulse” because, thanks to living in the countryside and growing our own food, I felt a renewed connection to the earth and nature. We seemed to be tapping into the life source of the land the way a Chinese doctor will listen for one’s life source by placing two fingers on the inside of one’s wrist to seek a person’s various pulse rates.

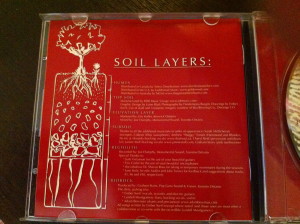

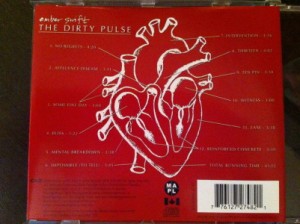

All of the drawings were my own and graphic design was, once again, put together by Liane Blad. I was especially proud of the soil layers on the inside cover where all the credits were read because of how layers of earth are not unlike layers of sound. (I felt so clever!) I also drew the heart on the back and used it like a diagram where I was pointing out the regions of the heart with the song titles.

This latter idea was inspired by some original artwork by Suzy Malik that I had seen years before. In fact, I never properly credited Suzy for this inspiration and I always regretted that oversight. Her artwork was also of a heart with its various cavities, looking like it had come straight out of a textbook, but with each label, she had a line of poetry that then each line carried down throughout the piece. I always loved how it seemed the poem’s words were assigned to the regions of the heart that were hurting, making each line all the more holistically heartfelt. It was for this reason that I wanted to assign the song titles to the heart, to show that the record was a full-hearted expression. So, thank you, Suzy!!

This latter idea was inspired by some original artwork by Suzy Malik that I had seen years before. In fact, I never properly credited Suzy for this inspiration and I always regretted that oversight. Her artwork was also of a heart with its various cavities, looking like it had come straight out of a textbook, but with each label, she had a line of poetry that then each line carried down throughout the piece. I always loved how it seemed the poem’s words were assigned to the regions of the heart that were hurting, making each line all the more holistically heartfelt. It was for this reason that I wanted to assign the song titles to the heart, to show that the record was a full-hearted expression. So, thank you, Suzy!!

(In fact, something I failed to mention in the “Stiltwalking” blog is that Suzy’s artwork had inspired me during the writing of “Boinked (the Bride)” as well. There’s a line in that song that comes straight from a piece of Suzy’s original artwork that is in my collection [pictured here on her website]. The original piece was a gift from Suzy that I have always treasured and is currently on the wall across from me here in Beijing. The line in the song is “Now I’ve come to your wedding in open-ended clothing” and the reference is, of course, to both the dress I was wearing and the fact that I don’t necessarily view femininity as defined via fashion! A little obscure until you check out the artwork and then you’ll get it!)

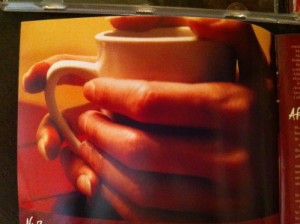

All the photos for this record were taken by Desdemona (Bunty) Burgin and the big background fingerprint on the cover and disc itself is hers (thanks B!) while the little ones are mine. I’ll never be cloaked from CSI agents ever again! In fact, I forgot they were mine until I noticed the picture of my hands holding the coffee cup in the liner notes. If you look carefully, not only can you see my acrylic nails that I used to have on my right hand to increase their strength and durability, but you can see the ink on my fingertips!

All the photos for this record were taken by Desdemona (Bunty) Burgin and the big background fingerprint on the cover and disc itself is hers (thanks B!) while the little ones are mine. I’ll never be cloaked from CSI agents ever again! In fact, I forgot they were mine until I noticed the picture of my hands holding the coffee cup in the liner notes. If you look carefully, not only can you see my acrylic nails that I used to have on my right hand to increase their strength and durability, but you can see the ink on my fingertips!

The tray card is a simple image of a skull and “bowling pin” cross bones. The song “Ten Pin” is a song that references bowling (and was meant to be a bit crude for those with good ears!) because this was the tail-end of a period in our lives when going bowling had been something very common on the road. In fact, back when we were working with Cheryl, we started a tradition of going bowling on our days off at least once or twice during a tour. Michelle came with us several times, as well, and then later we’d drag Adam into the bowling alleys. It was especially fun when we found an alley that was open all night and we could go after a particularly bad gig to release our negative energy onto the pins. This image comes from a small brewery in Colorado whose “Ten Pin Porter” beer we enjoyed on tour in 2006 and whose logo we were granted permission to use for the design: Ska Brewing Co (Durango, CO).

The tray card is a simple image of a skull and “bowling pin” cross bones. The song “Ten Pin” is a song that references bowling (and was meant to be a bit crude for those with good ears!) because this was the tail-end of a period in our lives when going bowling had been something very common on the road. In fact, back when we were working with Cheryl, we started a tradition of going bowling on our days off at least once or twice during a tour. Michelle came with us several times, as well, and then later we’d drag Adam into the bowling alleys. It was especially fun when we found an alley that was open all night and we could go after a particularly bad gig to release our negative energy onto the pins. This image comes from a small brewery in Colorado whose “Ten Pin Porter” beer we enjoyed on tour in 2006 and whose logo we were granted permission to use for the design: Ska Brewing Co (Durango, CO).

Overall, despite the fact that the album didn’t take me to some imaginary “higher level” in the industry, I was and am really happy with this recording. I believe that it’s an extremely strong collection of songs and I am still really proud to offer it to people to hear and/or purchase.

Graham agreed:

“I felt that it was your first true album…The album was strong melodically, had some positive statements to make and was sonically interesting to listen to… the album had the potential for you to reach a new, larger audience without alienating your existing one… I felt that The Dirty Pulse was a game changer.”

And how did I really want the rest of the game to change? I already spoke about wanting a more accessible record and I accomplished that. But, I also wanted to be home more. I wanted to do more gardening and home renovations, for example. I wanted the album to generate more of a following so that I could play larger venues but fewer shows. I had hoped that my management would help me try to get more licensing opportunities for the songs so that I could stay off the road and just sell the use of the songs (but they weren’t skilled in this area). For once, I felt that these songs weren’t just about preserving the live show’s energy but were more able to stand on their own; I hoped that this record would prove that I could stand on my own as a recording artist rather than just a touring artist with recordings that were live show souvenirs.

About six months after the release of the album in April of 2006 (at The El Mocombo in Toronto), having gone through a painfully difficult year in my personal relationship with Lyndell (described much more fully in this blog), I knew that the desire to do less of what I had been doing (touring) was achievable with or without a successful record or an effective team around me. In other words, this album wasn’t my golden egg or my silver bullet; my own will was the only guaranteed force that would and could change my circumstances. As I’d learned many times throughout my career to-date, when you really want something to get done, you’ve got to make it happen yourself.

That’s when I decided to organize my first-ever trip to China. I started planning in the late summer of 2006 and by April of 2007, I was on a plane. It was to be my first international solo journey ever. A rest, a retreat, a mission, a vacation — it was all of those things. I knew no one in Beijing except for a few names associated with email addresses. I had no gigs booked for three months. That also meant that I had no one to pay for three months and enough money saved up or donated for the journey that I was enrolled in a language refresher course and had my housing covered. I had also been employed to blog about the experience (earliest blogs in the 3-month series located here), so I was able to take on even more of the financial responsibilities at home even though I wasn’t going to be there. Everything just aligned to make that trip happen, like my whole life was getting a chiropractic adjustment. As a result, the liberating relaxation that settled into my neck muscles on that flight was enough to counter any trepidation or anxiety I may have had about heading to a foreign country with no one to greet me when I landed…